O BRASIL NA THE ECONOMIST

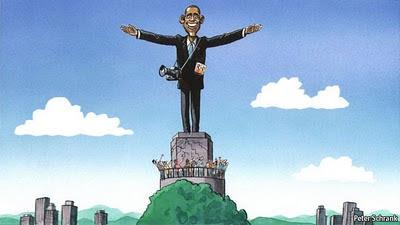

IN APRIL 2009, shortly after becoming president of the United States, Barack Obama attended a 34-country Summit of the Americas in Trinidad where he charmed those present—even Venezuela’s Hugo Chávez—with a call for the often fractious relationship between the United States and its neighbours to become an “equal partnership”. Two years on Mr Obama remains wildly popular with ordinary Latin Americans. But as he sets off on March 19th for his first trip to South America, he will find it hard to shake off a familiar air of mutual frustration.

IN APRIL 2009, shortly after becoming president of the United States, Barack Obama attended a 34-country Summit of the Americas in Trinidad where he charmed those present—even Venezuela’s Hugo Chávez—with a call for the often fractious relationship between the United States and its neighbours to become an “equal partnership”. Two years on Mr Obama remains wildly popular with ordinary Latin Americans. But as he sets off on March 19th for his first trip to South America, he will find it hard to shake off a familiar air of mutual frustration.For a start, part of Mr Obama’s mind will surely be elsewhere, on the wrangling in Washington over the budget and on the events in the Arab world and Japan. It must once have seemed a good idea to spend a weekend in Rio de Janeiro, watching a song-and-dance show in a favela. But to his domestic opponents it may not appear so.

For many South Americans, the United States is no longer the only game in town (if it ever was). Trade with China is booming. Many South American countries feel increasingly confident that they can make their own mark in the world. That is especially true of Brazil, the most important leg of Mr Obama’s trip.

Relations between the two countries have long been beset by minor niggles. But last year saw a big falling-out over policy towards Iran. Brazil, along with Turkey, voted against the UN resolution that tightened sanctions against Iran’s nuclear programme. Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva, Brazil’s then president, had earlier tried to broker a deal with Iran.

Brazil’s new president, Dilma Rousseff, is a protégée of Lula. But American diplomats are heartened by signs that she wants a fresh start. She has distanced herself from Iran, saying that she disagreed with Brazil’s previous abstention on votes condemning the country’s human-rights record. In a cabinet with many holdovers from Lula’s day, one change stands out: Celso Amorim, who was closely associated with the Iranian adventure, has been replaced as foreign minister by Antonio Patriota, a former ambassador to the United States who is married to an American.

Mr Obama and Ms Rousseff have potentially important business to do. They will sign agreements on scientific co-operation and the cross-recognition of patents. They will also talk of weightier matters. Mr Obama will want to push business opportunities for American firms; the United States has a rising trade surplus with Brazil and the White House is selling the visit as part of its efforts to revive the economy. Although Ms Rousseff has postponed a $6 billion order for fighter jets, Mr Obama will press the merits of Boeing F-18s (rather than France’s Rafale). The Brazilians want technology transferred in the eventual deal; they also want to sell to the Americans their own military-transport aircraft.

The Americans would like Brazil’s backing for their calls for China to revalue the yuan, though Brazil’s policymakers also blame the Federal Reserve’s loose monetary policy for the overvaluation of the real. Brazil wants the United States to end its subsidy to its inefficient corn-ethanol producers. That would open the market for Brazil’s sugar ethanol.

Brazil craves American support for its claim to a permanent seat on the UN Security Council. In November Mr Obama gave explicit backing to India’s claim. But the mistrust sown by Lula’s Iranian gambit means that the furthest the administration has gone is to say that it “admires” Brazil’s “growing global leadership” and “aspiration” to the seat, as Hillary Clinton, the secretary of state, put it last month.

Mr Obama’s next stop, in Chile, was to see an agreement on nuclear co-operation. But Chile, subject to earthquakes and tsunamis, is fast reconsidering the idea of nuclear power. Mr Obama’s last stop is El Salvador. Its president, Mauricio Funes, is a moderate, pro-American leftist; and Central America is beset with drug violence.

In Santiago Mr Obama is to give a speech setting out his vision of relations with Latin America. It will not be easy. The issues that matter most south of the border are migration, curbing America’s demand for drugs and export of guns, expanding trade and ending the American embargo against Cuba. On all of these the president is circumscribed by political deadlock in Washington.

The United States still matters in many ways in Latin America. Mr Obama’s own story inspires many in a region where blacks and indigenous people are often disadvantaged. He can be a powerful voice for democracy and human rights. But unless his words are backed up with some substance his appeal may fade.

- Lula Na Newsweek - EdiÇÃo De 30/03/2009

Lula, nosso Presidente, mais uma vez está nas páginas e também na capa da última edição da revista NEWSWEEK. Entrevistado pelo famoso jornalista Fareed Zakaria, "Lula quer lutar” é título da entrevista. Segundo o jornalista, depois de ser...

- Nova Etapa Nas Relações Eua E Brasil

Dilma Rousseff's visit to America Our friends in the South Apr 7th 2012, 14:52 by H.J. | SAO PAULO BRAZIL has probably never mattered more to America than it does now. America has probably never mattered less to Brazil. Not that relations are bad...

- Eclipse Of The Americas

"... The first Summit of the Americas, in 1994, was a moment of great promise. Thirty-four countries of the Western Hemisphere -- including the United States, plus many newly democratic states busily opening their economies -- signed a declaration affirming...

- Encontro G20

Ainda tem muitas diferenças entre os participantes: "...Europeans want universal banking regulations and broad changes in financial governance. The Bush administration stands opposed and Barack Obama, who is to replace Bush on Jan. 20, 2009, is considered...

- Crise Chega à Brasil

--"JUST a few months ago, Brazil’s economy was growing at its fastest pace since the mid-1990s, driven by record commodity prices and record credit growth. The country’s president, Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva, declared confidently that “Bush’s...